Earlier this year, Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist celebrated its 20th anniversary, and after recently re-reading the manga, I can confidently say it’s still one of the best pieces of art and storytelling ever created—just as impactful, and relevant, as when it was first released. The series has captured many, from seasoned anime and manga fans to novices who have had it recommended to them as a “gateway” series into anime and manga. But it’s not just a well-crafted, captivating tale of two brothers’ journey to regain their bodies; it’s also an intricately crafted criticism of capitalism, one in which nearly every facet of the story works to support this allegory so skillfully and elegantly that it elevates the series to the level of masterpiece.

The Truth That Lies Within The Truth

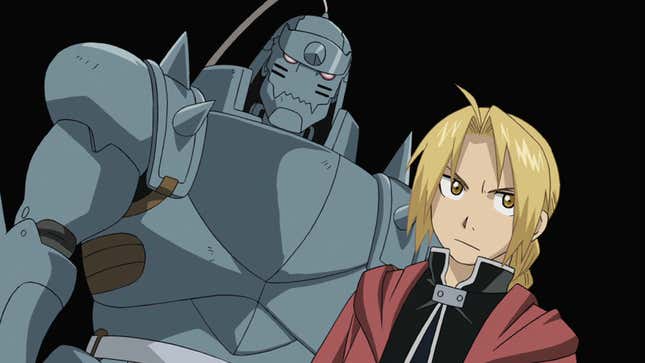

The series follows brothers Edward and Alphonse Elric, who attempted to bring their mother back to life using Alchemy—the science of understanding, deconstructing and reconstructing matter—the failed transmutation leaving Ed without his arm and leg and Al without a body, his soul bonded to an empty suit of armor. In order to get their bodies back, the brothers search for the Philosopher’s Stone, an object that grants the power to transmute without equivalent exchange, the ironclad alchemic law stating that in order to gain something, something of equal value must be lost. In pursuit of this goal, Ed becomes a State Alchemist of Amestris: alchemists who get government certification, access to records, and a consistent salary at the cost of being a “dog of the military.” In other words, they can be called upon to turn their work, or themselves, into weapons for the gain of their country.

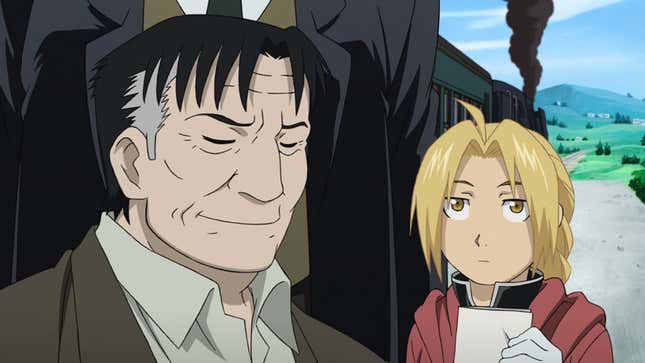

During their journey, they encounter Dr. Marcoh, a former State Alchemist who researched Philosopher’s Stones. He presents his coded research to the brothers and urges them to reach “the truth that lies within the truth.” This line refers to both decoding the research and moving forward from its truth, but it’s also Arakawa prompting you, the reader, to seek the truth behind the truth as well, to analyze the story, to seek the meaning behind it.

It’s important that this happens before Ed and Al discover the truth within Marcoh’s research, that Philosopher’s Stones are made by sacrificing human lives, because when they do, you are now primed to question what their findings mean in the context of the larger story. When you do, you can read Fullmetal Alchemist to be an allegory for capitalism—specifically, capitalism as a form of fascism. Through nearly every aspect of the manga (the story, the worldbuilding, the lore, the characters and their actions and arcs), the series explores and defines the intricate, complex, layered ways in which structural systems of oppression take from the many to give to the few.

Manga and anime storytelling often forgo subtlety, taking big swings early on with their themes, laying out everything early so they can expand the scope of what they are trying to say. That boldness is often one of the most appealing qualities of these stories, and Fullmetal Alchemist is a prime example.

Everything the series is trying to say is laid out in a smaller scale in the first five chapters, one of many virtues that speak to the manga as a masterpiece of craft and planning. In chapters 1 and 2 the manga lays the groundwork for all the themes, concepts, and worldbuilding of the story, with the brothers telling us what alchemy is and how it works, as well as introducing the concept of equivalent exchange and how the Philosopher’s Stone negates that. More importantly, in taking down the exploitative Father Cornello and his devious religion, we see them reveal and fight a manipulative system that’s using people’s faith to create an army of blind followers—a miniature version of the whole series’ arc.

The following chapters show Ed and Al taking down a corrupt military officer who’s exploiting a mining town, followed by a train-hijacking villain known as Bald. These chapters serve to show Ed and Al’s tenacity, wits, skills, and the fact that they are protagonists who can, and will, take down those doing harm.

In the following chapter we meet Shou Tucker, who invites Ed and Al into his home to study his bio-alchemic work. In a dark turn, this seemingly kind and caring father transmutes his daughter Nina and her dog into a talking chimera in a corrupted attempt to maintain his illustrious State Alchemist status, a title and position that is both coveted and stands as the main way for alchemists to make a living off of their studies. This chapter serves to tell the brothers, and us, not to trust every friendly face. Additionally, it ties into the search for the truth within the truth: Who can Ed and Al trust when the government was sacrificing humans to make philosopher’s stones?

These are the big swings, the laying out of plot and theme elements so they can be explored on a larger, more layered and intricate scale. Let’s dive into those layers.

Alchemy is representative of labor; in fact, it is literally a form of labor in the world of the story. If you want to get more specific, alchemy is labor under capitalism and/or fascism, not valued unless it makes money or serves the military/government; alchemists literally have to become “dogs of the military” to be paid well and have access to resources.

Now, think about the creation of a philosopher’s stone, made by sacrificing human lives. It’s not hard to see this as a form of labor exploitation or wage theft. Those in power benefit from the sacrifices of others, plain and simple. A philosopher’s stone itself in turn represents excessive wealth and the power that comes with it. The stone, like great wealth, does not negate the price of a transmutation, it just pays for it with the sacrifice of others. The obscenely wealthy do not pay less for their extravagant lifestyles, they just have so much ill-gotten wealth that their purchases are a drop in the bucket. Additionally, poisoning the earth doesn’t affect them, since they have used the sacrifices of others to ensure they never have to sacrifice their own comfort.

In this allegory, human transmutation is, in some form, attempting to use capitalism’s tools, mindset, and values to gain something for yourself. It’s not, however, the immoral intentions of the rich to simply amass more and more that drive this act. Rather, it’s the simple notion of wanting to get your fair share, and incorrectly believing, because of seemingly “fair” but actually hollow principles like equivalent exchange, that capitalist tools and methods are the way to do it.

Ed and Al attempt to resurrect their mother, providing their transmutation with all of the literal, physical ingredients that make up a human. But a human also has a soul, a value that cannot be determined or quantified, so the “equivalent exchange” is incomplete. Therefore, something had to be taken. Attempting to see people as just raw material to be used however one sees fit instead of as whole beings in and of themselves, with a mind, body, soul, and intrinsic value, is the perspective of capitalists, and the brothers, replicating that mindset in ignorance, were punished for it.

This is where “The Truth” comes in. The truth is that yes, there is a law of equivalent exchange, but it’s more literal and, well, truthful. If you are trying to make 11 with 10, The Truth will take the extra 1 from somewhere, be it Ed’s leg or Al’s body. Those who have attempted human transmutation pay a price, but those who pay the price with others’ sacrifices go unpunished, even gaining great power. Capitalism punishes the lower-class and impoverished who try to “break the rules,” (say, stealing food because they are starving) but literally gives rewards to the rich who do similar or worse forms of rule-breaking (harvesting immense wealth from the labor of people they work to the bone and pay a pittance, for instance). The wealthy work around having to pay any toll themselves by making others take the punishment for them.

Power, Sacrifice, And Who Pays The Price

Now let’s think about Father, the immortal secret ruler of Amestris and the main villain of the story. Father was once known as “the dwarf in the flask,” a homunculus (a being or human created by alchemy) made from the blood of Van Hohenheim, Ed and Al’s father who was born as a slave in the ancient city of Xerxes. After turning all of Xerxes into a philosopher’s stone that he and Hohenheim split, Father gained a humanoid form and the two became functionally immortal, also capable of transmuting anything regardless of the price. But, like any member of the rich elite, Father wanted more.

Father went on to found the country of Amestris for the sole purpose of expanding its borders, causing massive, bloody conflicts along the way and carving a giant transmutation circle underground so that he could sacrifice the millions of lives of Amestris to use as power to absorb and contain the power of god. Billionaires essentially want the same, seeking “the power of god” in the form of hoarded, ill-gotten wealth, bribing and lobbying the government to ensure their machinations of greed go unhindered. Additionally, he places a puppet in power, Wrath, one of many Homunculi he created. Wrath is known to the public as his human guise, President Fuhrer King Bradley. This system of power reflects how the leaders of many countries may pay lip service to the idea of serving all citizens while in truth maintaining a system that serves the rich.

In Amestris, the military and police enforce Father’s rule and preserve the status quo, and his underworld enforcers snuff out dissenters that could spark revolution, like Maes Hughes. Heck, even the alchemy of Amestris has limiters placed on it—a block on how much tectonic energy alchemists can access for their transmutations, representing how the poor and working class have limited access to resources that would allow them a fair share of wealth and security.

Father being a small creature stealing the power of others is also a pretty clear and biting commentary on fascists and the insanely wealthy: They are small-minded people, taking what others have created or profiting from their sacrifice.

Amestrian officers and military police serve to enforce the interests of the ruling class, and the Homunculi serve a similar role—a “necessary evil” that is “removed” from those in charge. Additionally, this is Father simply having others do the work for him here. He has done none of the labor himself and has even had others shoulder the burden of genocide and war so he can have even more power.

In fact, Father is literally using others’ loss as “payment” in the form of his “human sacrifices,” people who have paid a toll to see “the truth” and whom he needs in order to activate his nation-wide transmutation circle; Ed and Al, who lost their leg and body trying to bring their mother back; Izumi, who lost some of her internal organs trying to bring her stillborn child back; Hohenheim, who lost his humanity by Father’s manipulation; and Roy Mustang, who was forced to open the “Gate of Truth,” and pay the toll with his eyesight. Their losses are his gain, plain and simple.

But sacrifices can be voluntary or forced, used for good or for evil. Think of how characters use philosopher’s stones differently. Father uses his stone and power to gain more power, giving little thought to where the power will come from, concerned only with his need to take it. Hohenheim does the opposite. Hohenheim communes with the souls within them, gets to know them, talks to them and understands their individual hopes and dreams. He treats them like humans and, as a fellow human, asks to use their souls (which have no bodies to return to) to stop the person who did this to them in the first place, creating a counter transmutation circle to return Amestrian souls back to their bodies after Father absorbs the power of god, weakening him.

Ed and Al refuse to use a stone to get their bodies back after learning how they are made. However, they are both driven to use stones at some point. Ed uses Envy’s stone to get him, Ling and himself out of Gluttony’s weird stomach dimension, and Al uses one of Kimblee’s discarded stones to make the fight against Pride a little more fair. In both instances, the brothers feel deep guilt and seek to apologize to the souls they are using, or to ensure that their souls will not be used for evil purposes, but rather to fight evil.

Where Father sees these souls as a power source, Ed, Al and Hohenheim seek to see and treat them as the humans they were, to acknowledge their sacrifice and use it for good, not greed. The working-class, everyday citizens value the immeasurable worth of a human soul, while the greedy and powerful do not; they only value how those souls can benefit them, something applicable to both humans and dollars under capitalism.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. The manga’s criticisms and observations of the intricate and complex ways in which capitalism takes from the many to benefit the few are present in every detail and concept that play a part in the larger story. The futuristic prosthetics known as Automail represent the disabled and the overwhelming pressure people often face to get back into the workforce as soon as possible, even if they are suffering from chronic pain, illness or disability. Mechanics of automail limbs serve the role of healers (like doctors or nurses) who are necessary both to human health and, unfortunately, to maintaining parts of the capitalist machine. The Homunculi are born of Father, removed from him, and in turn represent how the wealthy believe themselves to be perfect—Greed in particular representing the complexity of want and desire in a capitalistic society that morally punishes wanting anything beyond basic needs.

Shou Tucker and Colonel Roy Mustang are both people far too invested in the system and game of capitalism to see another way out, Tucker believing status and gain to be more important than his own daughter, and Mustang falsely believing he can fix the problems of Amestris within a system built only to benefit the powerful. There’s even a major thematic thread concerning Al’s body and human autonomy under capitalism, those in power seeing his tireless and immortal armor body as a benefit while he, the individual, sees it as a cold, unfeeling, hellish existence.

All of this adds up to a manga that is not merely an allegory for capitalism, but one that’s stridently anti-capitalist. At every turn, Arakawa is making clear statements on the banality of the evil people driving capitalism (Father is a sad little creature making himself big and powerful by stealing power from others) and how only collective action and selfless, voluntary sacrifice can bring them down.

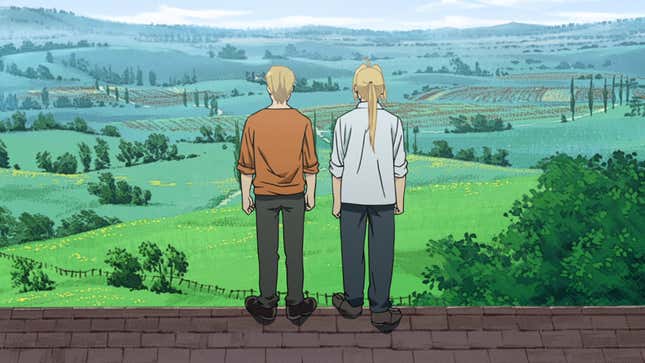

The series’ final fight addresses this. Al voluntarily sacrifices his soul so Ed can have his arm back and finish the fight against Father. This is a sacrifice Al chooses to make, one borne from good and love and kindness rather than a lust for power. Ed returns the favor, giving up his ability to use alchemy in exchange for Al getting his body and soul back; he not only makes a selfless, voluntary sacrifice for someone he loves, but he simultaneously casts away a symbolic tool of capitalism, creating a perfect thematic culmination of the series’ allegory. There’s even a fantastic endcap depicting Ed working with his hands on the roof of childhood friend/automail mechanic Winry Rockbell, appreciating the pros and cons of it. It’s tough, but he has a beautiful view of the countryside from up there, something he never would have gotten if he’d just used alchemy to fix it. It’s perfect.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, at the end of it all, Ed and Al are beginning to rethink equivalent exchange. No longer is it “take ten, give ten.” They now think of it as “take ten, add your one, give eleven.” They approach alchemy, a representation of labor, with the correct value of labor in mind, the extra part of the equation added by the alchemist or laborer himself.