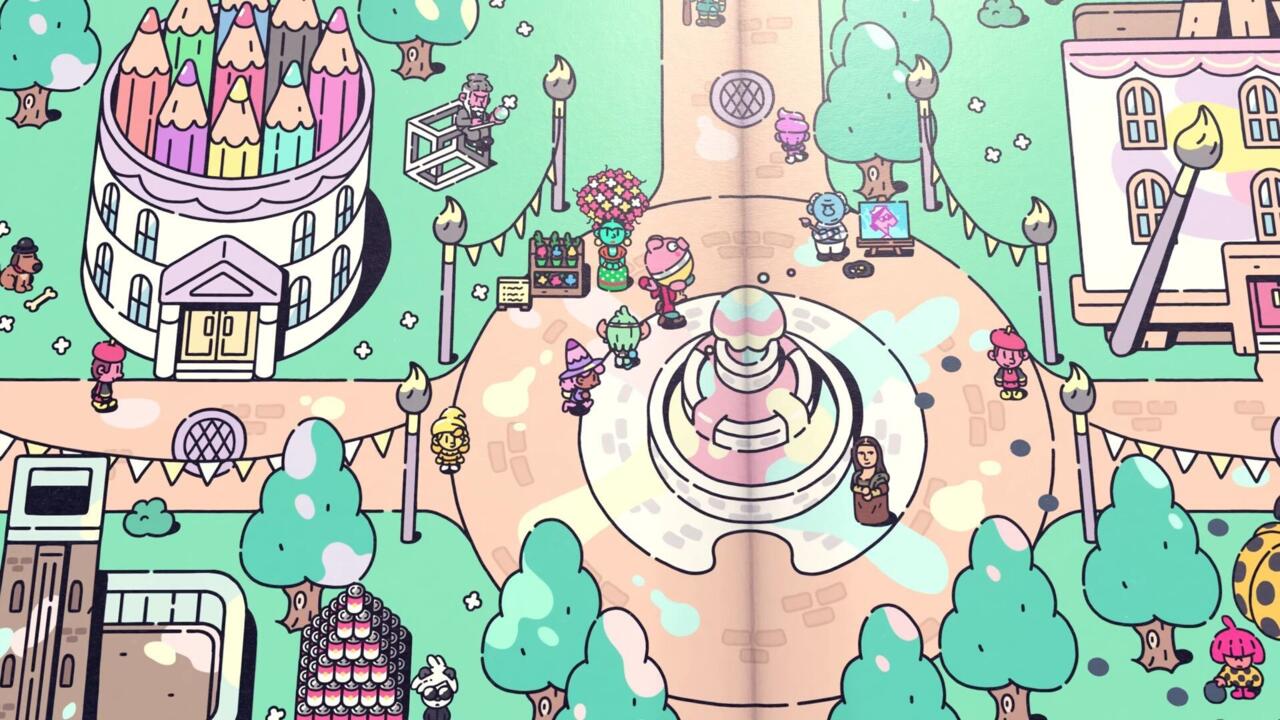

In the latest example of the company’s tongue-in-cheek approach to announcements, Devolver Digital has released the Devolver Delayed Showcase, which confirmed multiple games being pushed into 2024.

The three-minute video is a clear parody of Nintendo Direct, with similar graphics and an upbeat tone reminiscent of Nintendo’s regular update livestreams, only with the news that five Devolver-published games will be pushed to 2024. Those games are as follows:

- The Plucky Squire

- Stick It To The Stickman

- Skate Story

- Anger Foot

- Pepper Grinder

The video does end on good news, however, as it also confirms multiple projects that will remain on the 2023 schedule. The list of games staying in this year looks like this:

- Gunbrella

- Wizard With A Gun

- The Talos Principle 2

- The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood

- Karmazoo

- McPixel 3 DLC

With multiple games now set to release next year, we sat down with Devolver Digital head of marketing Nigel Lowrie and head of production Andrew Parsons to talk about the decision process behind a game’s delay, and how pushing a game back isn’t always a negative thing.

The two speak candidly about the conversations between developer and publisher regarding delays, how each side approaches the extra time being given to a project, and what the best ways to announce the news are. The duo also discusses how the teams reacted to Devolver Delayed, as well as the importance of maintaining a game’s overall quality is in deciding when to push a game back.

This interview was recorded via Zoom and edited for clarity.

What sort of approach do you take when it comes to announcing a delay? Do you try to have a theme like this Devolver Delayed every time?

Nigel Lowrie: There’s not really a theme around announcing delays, like the devs just wanted to quietly put it out there and hope no one gets too angry. I think the thought was, “Hey, delays happen all the time, how often do games hit their dates, so why not have fun with it?” A lot of our inspirations for anything Devolver Direct are, of course, Nintendo Directs, and they’re all quite cheery, as they should be. They’re delivering exciting news, so we were like, “Why don’t we deliver the exciting news that this game you’re waiting for has been delayed?”

What’s the other way to do it, just announce it like “Oh, we’re so sad, we’re so sorry?” No, this is for the best, and as you’ll see in the video, the news is delivered with that sort of explanation. This was born from that idea of “Why not have fun with it” and that’s what we try to do all the time, with us and our developers. Just have fun with the news you have to deliver, and make it more interesting than the basic thing.

What was the developers’ reaction to taking the Devolver Delayed approach with their news? Were they receptive? Were any of them hesitant?

Lowrie: I think Andrew might have a different thought, but we actually just made it first, as it was simple to make, and then shared it with them to get their approval. We wanted to show the tone of it, and everyone approved it immediately and thought it was a fun way to do it. They get it, they don’t want to delay their games either, but they love that there’s a positive spin from their publisher on it.

Andrew Parsons: Nigel is right; there’s an amount of contrition in the industry whenever it comes to delivering bad news, when in reality, our developers are responsible people, and whenever we have conversations about what we think might need more time, or we say to them “Do you think you need more time,” the conversation is always a two-way discussion. When you bring that out into the light and say, “Cool, this is something everybody does, everybody poops,” there’s no reason to be contrite or try to hide from it. Some of these guys have been working in games for a long time, and they know that any opportunity to communicate with people–even if it’s with bad news–is a good one.

Let’s talk about why these particular games are getting pushed back. When did the teams approach you with the delays, and what are some of the reasons behind them?

Lowrie: I think, for this conversation, it’s better to treat them all as a group, as they all have various reasons for the delays. It’s like anything in your life or my life; there’s work stuff and personal life stuff, people have babies, get sick, etc. COVID was obviously a big deal. There’s a lot of different reasons for a delay.

It’s not always the developer coming to us saying “We’re going to be late;” sometimes it’s Andrew and his production team. We don’t want people rushing to the end; that makes for a bad product with cuts, things done improperly, etc., and it doesn’t help the quality of life for the developer, for us, or for the game itself. Andrew and his team then step in and say, “Look, you have a lot to do, and you say you can do it in X amount of time, but maybe you need a little more time.” Everything from localization to testing must be considered; I know that’s a big topic in the general gaming zeitgeist right now: “Was this game even tested?” Of course it was, but how much, how thoroughly, and was enough time given to correct certain things? We want to make sure those things happen.

Sometimes it’s a matter of content: Could there be more, could they flesh out an area the team is really enjoying, etc.? Other times it’s localization or porting, which can take longer than you’d think depending on the complexities. I don’t think these are necessarily new, but the combination of things add up and lead us to say, “Let’s not rush this, let’s get all of these things done correctly.”

Parsons: The emphasis for us, as it’s always been, is on quality. Quality is not just doing things well or to a high standard, it’s doing things in every aspect of the game to a consistent level of quality. What tends to happen with our developers, because they’re super talented, is they will go through phases of development where they’ll say, “We’re working on this, and we think we have something good,” and then two-thirds of the way through development they’ll come to us and say, “Look, we think we have something really special, and we want to start working on that.” We the production team will rally around them, asking what we all can collectively do to make that a reality.

Let’s say the previous example is a gameplay mechanic, and it’s complicated. It needs sounds, animations, etc. All of those things need to be at the same level of consistent quality as everything else in the game, which they’ve been working on for a year. It’s not about “Hey guys, we’re going to add something new,” it’s having the conversation like, “Something new sounds fantastic, but what is it going to take to get it to the same level of quality across the board?” That’s alchemy, it’s a really intimate and incremental process.

Lowrie: This raises a good point: Devolver is known, at least with our developers, for the creative freedom we allow them. Sometimes, that will make them want to explore things in their game more. One of the more famous examples is The Talos Principle, the first-person puzzle game from Croteam. Croteam was working on Serious Sam 4, and one day they sent us this build and told us they’ve come up with a really cool puzzle mechanic in Serious Sam 4, but it doesn’t fit in a first-person shooter anymore, it’s too complex. They explained that they made this build in their spare time, and they’re calling it The Talos Principle, and here’s the basic narrative and 10 puzzles to check out. We’re thinking, “Holy crap, they’ve just made another game,” and it was great! That delay of Serious Sam 4 came because the devs were given so much freedom to create different things, they tried something they loved and ended up making their most critically acclaimed game.

More recently, we have a game coming out this summer called The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood, made by a team called Deconstructeam. After their last game, The Red Strings Club, launched, they began working on Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood, so it’s been in the works for years now, but at some point the team said “We’re not feeling it creatively right now, we’ve hit some roadblocks creatively,” to which we said “Take your time,” and that was two years ago.

Parsons: That’s a great example, because some of the aspects of that game have been within the team for a long time now; like the ideas, concepts, some of the mechanics, etc. However, taking the time to glue those parts together in a way that’s consistent is what makes it feel like a coherent, high-quality product. It’s all well and good to say “I have this idea, I’m going to work on it,” but bringing it to that high-quality standard is the job, and it comes with multiple different technical requirements. It’s a big job.

Does the internal Devolver team suggest a game need more time, or are the separate dev teams usually the ones to suggest a delay?

Parsons: It does differ, it varies for every developer. We work with teams who are just a couple of people, and then we work with really big teams. It varies all the time. My function as head of production is to have an overview of a game, and then chat with a developer and ask them if they need more time. The developers, as I said in the beginning, are super responsible and great partners to work with; they’re the heart and soul of this whole endeavor. They always feel like it could be a hard conversation, but we want to make it as easy as possible for them.

As far as I’m concerned, no matter how much marketing or business development get mad at me, we’re going for quality here, and if I’ve discussed it with the devs, and we agree, then we give them more time. Sometimes it’s a bargaining session–the dev team wants this many months, we offer a different amount, and we come to an agreement–but it’s always a question of, “What do you think you need to get to the quality bar you’re aiming for?” That tends to be the middle ground, our baseline, and then we figure out what else we need to do to make it a reality.

The word “delay,” from a consumer perspective, implies there’s something wrong with the game being pushed back, but here it sounds like new and cool things are being added and causing the delay. What are you guys trying to do to try and take the negative connotation from the word “delay?”

Lowrie: We’re certainly not going to speak for all developers and publishers, because I think there’s certain situations where people delay games because they’ve been doing QA and no one’s having fun with it, so they have to be restructured. I think we do a pretty good job early on at signing games that have a clear vision of why they’re fun and interesting from the beginning. Maybe we, in a good way, are an exception in that our delays are usually just to improve the quality of the experience, to start pushing out on the places that are really working well, and making sure the quality of life stays intact.

This gets into Devolver from a business philosophy standpoint: The reason we have so many developers wanting to work with us again and again is because the experience was a good one. They didn’t get to the end of a game’s development cycle and think, “I hated that experience, I don’t care how much success or fame I see from it, that was miserable.” It’s important to us that they have their lives still, in that they’re not working 80-hour weeks just to get this game out. Some of them we can’t stop, they’re just focused and it’s what they want to do, but we try our best. We also want to space things out; we’re not trying to give out press review codes last minute, we’re not trying to get things to streamers last-minute, stuff like that. It happens, for sure, but we want to do our best to limit or mitigate that risk. You’re right that it’s definitely a creative thing, but I don’t want to dismiss us making sure they have a good time making this game, while also feeling like they can still breathe.

We’ve had situations where changes were made in haste at the last minute, be it due to time pressure, the developer themselves, whatever the reason, and the game suffered because of it. These were never catastrophic, but they were things we looked at in retrospect and said,” Yeah, we made all of that very quickly, it probably shouldn’t have been, and we see how the game suffered.” We’ve done our best these past 14 years to keep learning from situations like this, and ultimately we’ll sit down, explain why a game should be delayed, and emphasize that it’s for the best for the game and the developers.

We don’t often have times where we look at something and think, “Oh no, this is a disaster” and delay it for six months to a year. Our delays are mostly positive; it’s not because something is bad, it’s because we want to give them the most time to make it the best it can be. They’ve been working for 5-6 years in some cases, what’s three months more? Doing all of that work just to fumble at the end just seems silly.

Parsons: To Nigel’s point about letting the developer breathe, the game they’re making needs time to breathe as well. Can delays be seen as a good thing? Part of our job is building an eclectic roster of games, and I’m so proud of what we have. We always feel like we can stand behind the games that we select to publish. Not all of them are going to fight toe-to-toe with Red Dead Redemption or Street Fighter on Steam. Eventually, we get to a point where we say, “We’re good with it,” and then we look at the upcoming schedule. Maybe there’s something we want to avoid, like a summer sale or a big release, because we want to get the game the oxygen it needs to have the best chance to succeed. We want people’s eyes on it, we want people to devote time to it. We understand that people who buy games have limited time and money, so we want to make sure that if they’re going to make a Devolver choice, for one of our developer’s games, we want to make sure it has space around it. Just take a look at the release schedule for this year: It’s crowded out there.

Lowrie: There’s a period of time this year, in September, where Mortal Kombat 1, Party Animals, Payday 3, and Lies of P are all within 48 hours of each other. We had a game–we didn’t say publicly which one–where we were targeting that timeframe, and we’re now moving it back a couple of weeks. Not because we don’t believe in the game, we absolutely do, but what’s the point of picking a fight with a lineup like that if you can avoid it? We don’t want to have to ask our fan base to choose between us and some other excellent games–and those are excellent games, I want to play all of those games.

Parsons: This brings up an important concept when talking about delays. Some of them are internal; they come from us as the partner to the developer, some are vice versa and come from the developer, but in both cases it’s a conversation we have. Some delay reasons are external; during COVID, for example, there were genuine manufacturing problems.

With all of the first parties, there’s a certification process, which is usually completed when a dev team announces they’ve “gone gold.” During COVID, those certification periods went from being completed in days to weeks, so all of our previous forecasting–the game will be ready on day X, we can put it out on day Y–went out the window immediately, and that build-up lasted for a couple of years. Whenever a publisher or developer make the announcement, it feels like something they’ve decided to do, whereas sometimes there’s nothing that could have been done about it, it was out of their control.

Has there ever been a time where you suggested a team take more time with a game, and the dev team flat out refused? If so, how do you mitigate that situation without souring the entire relationship?

Parsons: It’s not common, I will say. The most common way that conversation goes is us saying, “What do you think about this,” and the dev–who sometimes have been working on games for years, remember–are very disappointed that they’re not able to talk about or release a game yet. The conversation then quickly moves on to, now that we’ve all agreed to take more time, what we can do productively to make the most of that time. If we’re lucky, that’s also more time for the marketing crew to gather round. What we tend not to do is change the game itself too much.

All of our developers tread this delicate balance between experimentation and uncertainty, it’s what makes them unique. That’s from conception all the way to release, so adding delays or any extra time to that schedule always makes people feel uneasy, even if they’re totally on board with it. It becomes a matter of everyone staying calm, mainly because if the game goes really well, the team is going to be very busy when it comes out with patches and interviews and the like, so enjoy the delay while you can.

Another common misconception revolves around downloadable content, or the idea that content is specifically held back from the game and released later. How do delays, when they occur, affect post-launch plans? Is that stuff planned ahead of time and then shelved, or do they get to the finish line and then start planning extra content?

Lowrie: It depends on the project, but if there’s a delay due to a busy competitive schedule like we mentioned earlier, the team can start working on the DLC or other post-launch content. People do work on post-release content when delays happen that aren’t for reasons directly related to the base game. If the base game needs more work, they’ll focus on the base game and put the DLC to the side. We work with relatively small teams as Andrew pointed out, and we don’t normally have situations where there’s a separate team working on DLC concurrently.

Cult Of The Lamb is a good example; that game started with a team of four, they’re at maybe seven people now, and they’ve had one major update along with a few minor ones, and more updates still planned. They had to finish the base game before they started working on the other stuff. However, if there’s time, and the game’s coming out in a month or two, yeah they’ll start working on those things. Bigger publishers have the ability to work on those things concurrently, but those are teams with 400 people working on a single game.

Parsons: To build on the Cult Of The Lamb example, Relics Of The Old Faith was the first big update which came out in Spring of this year. There are aspects of that update which the team had in mind for quite some time, but because they’re great developers who are incredibly dedicated and have their heads screwed on right, they knew what they needed to do to get the base game right. They knew they wanted to do those things, and they saw the community chatting about those aspects on Discord or through Steam Next Fest feedback and asking why they’re not in the game. However, they also knew they can’t work on that stuff while they’re trying to get the basic things which every player is going to have as crisp as possible.

If developers start to think, “We have this delay, let’s go back and change this or that,” there’s a big risk involved that one small aspect of the game you’re putting out might not be as good as the rest of the game you’re putting out.

When does the team decide whether a new idea is worth adding to the game they’re working on or, as in the case of The Talos Principle, is it worthy of its own project? Does the development team approach you with that, or do you sometimes identify those things?

Lowrie: It’s a little bit of both. There are times where they’ve talked about it internally and then approach us. Sometimes it’s content, sometimes it’s platforms–a team could say they really want to bring a game to Switch at the same time as PC when it was originally just PC. We’ll sit down with them–our finance team, marketing, production, everyone–and we’ll weigh in with pros and cons, in order to figure out how much time it’s going to take to add in a feature or platform. There’s no science to it, but sometimes we do have that gut feeling where “Yeah, this game could use multiplayer” or “Wow, this game should have this mode” and we’ll weigh those out with the developer.

Parsons: As much as possible, we try to have a coordinated effort with the teams. It’s not just the devs saying “We’re going to do this or patch that;” if that’s going to happen, we want to mobilize the marketing crew, we want to talk to PR, and make sure the assets are all correct, and the message is that people who are already into the game say “Cool, I’m going to get more of that thing I like.” I’m a producer, so my life is spent looking at calendars and spreadsheets, and I’ve learned that once you add in one day for something, you might as well add in three days instead. We think something is going to take one day to decide, and suddenly it’s day five and we still haven’t made that decision. Getting everyone rallied around something can take a little time, but once you’ve done it, you can get a nice across-the-board message that goes out on six different platforms at once like Steam, Twitter, your nan on Facebook, even Threads.

Then, you have to make sure whatever you’re adding to the game is localized and QA’d. You can’t just come up with an idea and just bang it into the game, it’s a coordination of things that can sometimes cause delays, but from a fan’s point of view, all they see is a coordinated message.

The products discussed here were independently chosen by our editors.

GameSpot may get a share of the revenue if you buy anything featured on our site.