My dad played video games before most people knew there were video games to play.

I think we got our off-brand Atari 2600 in 1979. This is one of so very many details I desperately wish I could fact check, but never will. Because in 2016, my dad—Hugh Walker—unexpectedly dropped dead on the sidewalk at the age of 66. He was walking home from breakfast at a friend’s, and then he wasn’t any more. And with him went nearly seven decades of encyclopedic information on every detail of world history, and forensic knowledge of the UK game development scene of the 1980s.

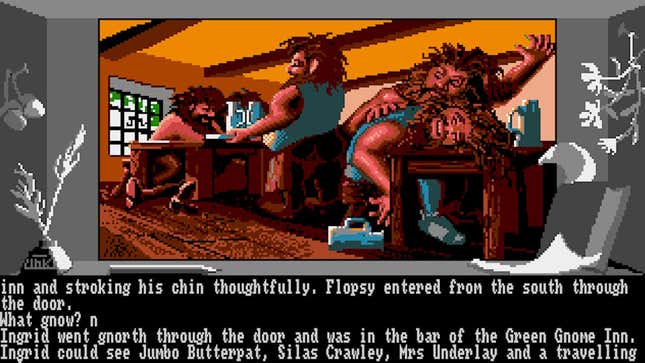

My dad was like a cuddly toy in many respects, but one in particular was the metaphorical hoop on a length of string protruding from his back, that when pulled would unleash a breathless spiel of informed and entertaining knowledge. It was always a monologue, but it was generally worth listening to. It might be that you’d accidentally trigger something on the royal turbulence of the 1500s, but it could equally be the origins of film-license specialists Ocean Software, or personal anecdotes on how he became friends with the developers at Level 9, developers behind text adventures like Jewels of Darkness and Ingrid Strikes Back.

In 1981, Hugh Walker got the first ever affordable (although we could barely afford it) mass-produced home computer, the ZX-81. In 1982 he was sent a pre-release ZX Spectrum 48K to review for a magazine. In 1984 he had a game published, a “type-in” for a magazine, called Warlock. (I can make a strong argument for it being the first ever roguelite.) He regularly contributed to a popular UK fanzine called Adventure Probe (in 1990 he wrote an against-the-grain lengthy feature arguing in favor of “character interaction” being included in games). I remember helping him playtest unreleased text adventures. And he’d come back from big gaming events like ECTS with bags of swag—all of which is made much stranger when you learn that he didn’t work with computers, nor have anything to do with the gaming industry. He was an NHS dentist (as in, the badly paid kind)—computers and gaming were simply a hobby.

I was born in 1977, so I wasn’t even in school when computers first entered our house. Because of dad’s connections, I reviewed my first video game at the age of 11. It’s some messed up superhero origin story stuff, given my job now, minus the “super” and “hero” parts. And of course, growing up surrounded by gaming is the most normal thing imaginable now, but it was much more rare back then.

Games were a key part of my relationship with my dad. The first time I knew he was capable of being scared was watching his hand shake on the mouse as he battled the dragon on level 13 of FTL’s seminal 1987 RPG, Dungeon Master. He demonstrated his enormous tolerance of me as I begged him for a go in the middle of his game of UFO: Enemy Unknown and would get his entire squad killed because I wanted to play it like an arcade game. I learned of his enormous, inexplicable patience, as I would sit next to him, watching him play 1991’s original Civilization, pestering him to start a war rather than working out wheat prices or whatever the hell that boring-ass game had you do.

The great gaming schism

As I grew through childhood, so did games. From white text on a black screen, they gained crude images, then entire games were made from these moving sprites. And as I became a teenager, video games very appositely represented the ways in which I deviated from my father, as is tradition. Adventures had diverged, evolving into both graphic adventures and RPGs. I went left, he went right. I played every single Sierra and LucasArts game, plus all their knock-offs (as well as FPS games as well, of course), occupying his 486 PC until my bedtime mercifully returned his machine to him, when he would then be sat surrounded by hand-drawn maps on squared paper as he explored dungeon after dungeon. SSI’s Advanced Dungeons & Dragons games occupied him far more than was reasonable, alongside stone-cold classics like Betrayal At Krondor and Lands of Lore.

But we still intersected, like slot cars on a crossover track. The collisions were when we both wanted to play the same game at the same time, as was certainly the case for the all-time great Looking Glass title, Ultima Underworld II, the first game we bought for dad’s shiny new PC. (It pushed all 2 MB of RAM to the limits.) But primarily, dad lost his patience for obscure puzzles, and I lost my patience for mixing potions. It wouldn’t be until BioWare started flexing (with Baldur’s Gate) that I’d rediscover the RPG, but that would be the same time the genre lost dad’s interest.

Thankfully for him, The Elder Scrolls never went away. He adored all of them, and somehow without ever learning how to install a mod. And he loved none more than Skyrim. After he died, one of the admin jobs I had to do was sort his PC, which was still logged into his Steam account. He had hundreds of hours on Skyrim. Although the “1,263 hours on record” for X-COM: UFO Defense suggests that maybe he left that running in the background rather often. Video games had been a permanent accompaniment for him (along with my mum, I should probably add) for 35 years.

My dad was a good man. One of the true ones. He was normal, he messed up, he sometimes made bad choices (he bought an Atari ST instead of an Amiga for goodness sake), and he and I shared similar struggles with anxiety and mental health. But he was a truly good person, who would fight for those with less, who was capable of changing his mind when he recognized his own prejudice, and who made sure the people around them knew they were loved. He had a solid grounding in his morality, and I knew he was there for me, had my back.

I very strongly remember in 2015, just under a year before he died, and very shortly before he retired, a great example of his just being there when I needed him. I had, that day, published a somewhat infamous interview with notorious game developer, Peter Molyneux. It was shortly after it had become apparent that Molyneux was never going to finish the Kickstarter-backed game Godus, nor fulfill his promises toCuriosity winner Bryan Henderson, and I wanted to try to hold the man to account.

The internet’s reaction was predictably large, and despite almost every claim Molyneux made during the interview itself having since been proven to also be untrue, there was a grim backlash. I had spent the day receiving some of the most horrendous abuse on Twitter and in my email and via my website. At the same time, I had terrible toothache and—with some irony—had to travel across the country to Guildford, where my parents lived, and where Molyneux was based. And dad just understood. He knew I had done the right thing, that I had stood up for what was true and fair, and he made that clear to me. He hugged me, he made me feel safe. He also fixed my tooth.

All the way until his untimely end, we would chat about video games. As dad got older, his interests narrowed, and his tolerance for burgeoning genres lessened. Despite loving the Elder Scrolls so much, he bounced off of Fallout 3 and 4. I would tease him for just replaying the same five games over and over, and especially for his habit of endlessly restarting things like Civ until he found some impossible perfect route. He was the sort of person who’d finish every RPG with a backpack full of potions that he was saving for the right time, then start over and do the exact same thing again.

But we did overlap one final time. It was the completely wonderful Legends of Grimrock, a traditional dungeon-crawling RPG made in tribute to the mighty Dungeon Master. It was so perfect, evoking the memories we both had from 1987, of him playing that game on our Atari ST sat at the kitchen counter, and me, nine years old, watching in awe.

I was playing an early review copy of Grimrock, and managed to get the lovely developers—Almost Human—to send me a second pre-release Steam code so dad could play too. I then commissioned him to write about it for RPS, leading to a series of completely barmy articles called A Dad In A Dungeon.

I really miss dad. Obviously I miss having my father, miss being able to talk nonsense with him on the phone or in person late into the night, and I lament the loss of the vast amounts of knowledge he carried. But the thing that brings this home for me more often than anything else is video games. He would have played Starfield. He would have had a lot more patience for it than I do, and likely motivated me to stick with it past its abysmal beginning. He would have watched Amazon’s Fallout, but been incapable of discussing it without repeatedly explaining to me why he didn’t get on with the games. For some reason, Firaxis carried on making Civilization games after he died, which doesn’t even make sense to me. Why did they bother with VI, when dad was never going to get to play it? I want to pick up the phone and pester him to stop being stupid about it and play Baldur’s Gate 3. And you know what? I absolutely cannot remember if he ever played Dragon Age: Origins, and there’s literally nothing I can do to find out.

What do I want anyone to get from this meandering, shapeless thing? Honestly, that you learn my dad was a good man. He deserves people to know. And that such a person eventually goes away, often very suddenly. It’s worth knowing. Thanks dad. Happy Father’s Day.

.