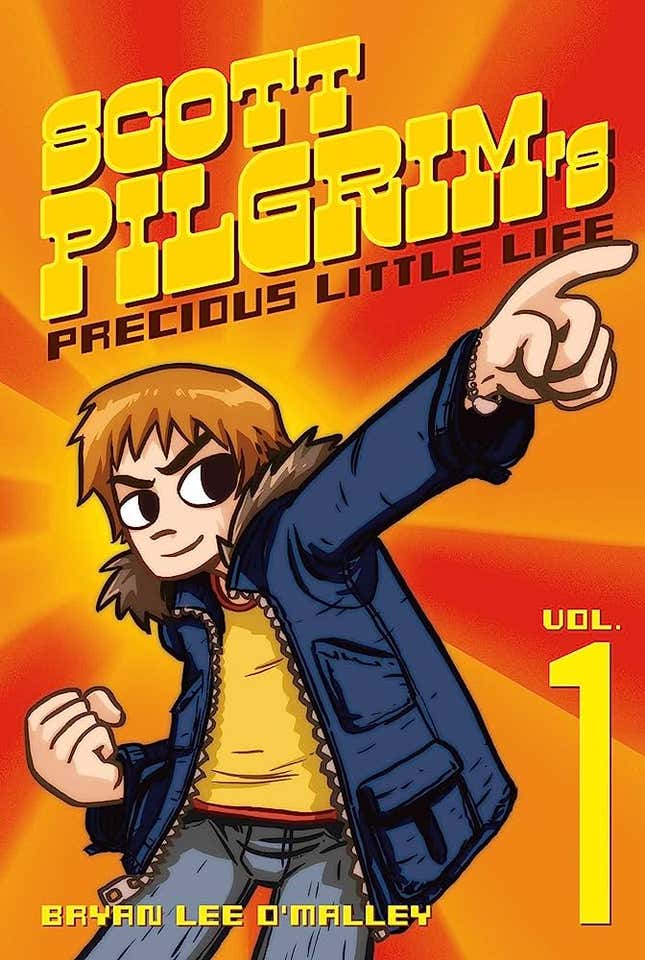

Scott Pilgrim Takes Off, the new animated series based on Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novels, is out on Netflix. The eight-episode series reunites the voice cast of the 2010 live-action movie Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and is a hilarious blend of the series’ quick wit and well-measured pop culture references. All of this sounds like a recipe for success, right? Well, it’s a little more complicated.

You might have heard around the internet that some fans are not too happy with the new anime, but you might not understand why. It’s a long story that requires us to examine Scott Pilgrim as a text, its fandom, and the specific way Scott Pilgrim Takes Off subverts expectations. So grab your giant hammers and bass guitars, it’s time to unpack the story of Scott Pilgrim, its fandom, and what it’s like to reckon with all of that in 2023.

What is Scott Pilgrim about?

For those just tuning in, Scott Pilgrim is about the titular 22-year-old who likes video games, plays bass in his band called Sex Bob-Omb, and is dating a 17-year-old girl named Knives Chau. Put a pin in that last one. Meanwhile, he meets a more age-appropriate girl named Ramona Flowers who just moved to Toronto and is recently out of a bad relationship. Scott starts a relationship with Ramona before ending his relationship with Knives. There’s at least one problem here: He must defeat Flowers’ seven evil exes before they can date.

What follows is big, flashy, stylized fights with the evil exes alongside Scott dealing with his interpersonal drama, trying to nurture his relationship with Ramona, and plenty of quips, gags, and guffaws. But despite the over-the-top, often slapstick nature of the writing and presentation, the Scott Pilgrim books really dug into the ramifications of Scott’s chaotic, destructive nature.

Much of Scott Pilgrim’s pop culture persistence is attributed to the 2010 film adaptation Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, which, despite a disappointing box office performance, has gone on to be a cult classic. Arrested Development star Michael Cera seemed like an odd choice for our titular fuck-up, but I can’t even read the comics these days without hearing his voice in my head when Scott speaks. The movie captures a lot of the humor, character, and style of the source material, elevated by a quality cast that is kind of hard to believe 13 years later.

Cera and Mary Elizabeth Winstead play Scott and Ramona alongside some other now-huge names, like Anna Kendrick, Brie Larson, Aubrey Plaza, and Chris Evans. But the movie isn’t a 1:1 adaptation of the graphic novels, and as such, it suffers some blind spots in its overarching narrative. The Scott Pilgrim books take place over the course of several months, and the film condenses all of the drama into a few days. Entire relationships, emotional arcs, and story beats are either haphazardly shoved into the movie’s brisk two-hour runtime or, as is the case with like Stephen Stills’ coming-out story, omitted entirely. So despite the movie being beloved, some fans (maybe even myself) haven’t felt like Scott Pilgrim has gotten a proper adaptation that fully explored all its nuance.

Now we have Netflix’s Scott Pilgrim Takes Off. It’s eight episodes long, with a total runtime about twice as long as Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. This new show could have, theoretically, better explored the graphic novels’ original story. But Netflix’s series doesn’t do that. It flips the original story on its head and examines it through the eyes of Ramona while Scott…takes off for half the show’s run.

Why Scott Pilgrim Takes Off is effective and necessary

While yes, I felt some initial disappointment that we weren’t getting a more fleshed-out adaptation of Scott Pilgrim, I came around very quickly on the show’s subversive, metatextual take on its story. This twist is a great way to give Ramona, who the film adaptation did especially dirty, a chance to examine her own issues with abandonment, demonizing her exes, and absolving herself of the pain she had caused…just as Scott got to do in the original story. And while I, and other fans, might’ve needed some convincing, it sounds like O’Malley was wholly uninterested in doing a rote retelling of the source material, telling Variety that doing so would have felt “like death.”

Instead of recounting Scott’s fights with Ramona’s exes, Takes Off has its leading lady investigating our hero’s disappearance after his apparent loss in the first fight against evil ex Matthew Patel, who dated Ramona for a week and a half in middle school. Scott’s supposed “death” sends the entire story of the original books into a tailspin, and Ramona spends the majority of the show reconciling with her exes and figuring out that, despite the branding, none of them were really “evil” after all, and she was just as much an “evil ex” to them.

While Ramona gets her time in the spotlight, Scott, in his somewhat limited screen time, is still a focal point in the show’s second half. It turns out he didn’t lose the fight against Matthew, but instead was pulled out of it by a 37-year-old future version of himself who’s going through a messy divorce with Ramona. To old Scott, defeating the evil exes and being with Ramona was the biggest mistake of his life, because if he’d never been with her, he wouldn’t be going through the pain he’s experiencing from the divorce.

This idea weaves well into Scott Pilgrim Takes Off’s themes while examining the inherent destructive selfishness that has been part of his character since the graphic novels. Though Ramona spends all of the show reckoning with how exes demonize each other, frequently they are just other, normal human beings trying to make it work like the rest of us. Meanwhile, Scott’s older self has not come to that realization, and views Ramona and his prior, loving relationship with her as nothing but a waste. He’d rather it never happened than fight to save it, which does not paint a flattering portrait of the elder Scott. He centers his own pain while ignoring the damage he’s caused others, and it’s only after young Scott sees this version of himself that he reflects on some of the heinous shit he’s already done, like dating a high schooler.

All of this makes for some really clever metatextual commentary on the basis Scott Pilgrim is built on. The original graphic novel examines these ideas in its six-issue run, but it feels like the movie lets many of these conflicts fall through the cracks, boiling ideas like Nega Scott, a physical manifestation of all of Scott’s flaws, down to short gags. Scott Pilgrim Takes Off manages to break down all Scott’s flaws in new ways, so while it’s not a direct adaptation of the graphic novels, the new show is definitely in conversation with everything that’s come before.

Why are some fans disappointed with Scott Pilgrim Takes Off?

So what’s the problem? There are a few sources of possible ire. Pushing aside with all our might that there is likely a contingent of fans who just hate women—that are mad Ramona took the spotlight this time, approved of Scott Pilgrim’s detestable behavior, and said “he’s just like me, FR” because he speaks in video game references and has the hots for women way out of his league—there are at least some arguments to be made.

Part of the issue stems from Netflix’s lack of transparency about what Scott Pilgrim Takes Off would be. This is a recurring theme for metatextual work like Final Fantasy VII Remake and the Rebuild of Evangelion films: initially they’re presented as retellings of beloved stories, only for it to become clear at some later point that they’re going to take more than a few liberties and tell a different story entirely. Moments like Scott seemingly losing his fight against Matthew Patel are effective because they subvert your expectations. They’re a twist just as much as any other in storytelling, but they happen when returning fans expect comfort food. That disruption, especially one that makes you reconsider something you’ve loved for a long time, creates a specific friction that can be difficult to manage.

Speaking personally, I’ve had different reactions to this kind of twist depending on the project. Rebuild of Evangelion felt like a creator reflecting on how his own pain put characters through the wringer in the original work, but Final Fantasy VII Remake has me a lot more hesitant largely because I haven’t enjoyed Square Enix’s attempts to further expand various Final Fantasy universes, so I’m less eager to see that company’s take on a metatextual reexamining of its classic RPG. But hey, Final Fantasy VII Rebirth may reassure me.

Stories like Scott Pilgrim Takes Off are meant to push against long-held fandom perceptions. The entire point of taking an established story off the rails is to make you reconsider what it all meant. Was it too subtle the first time about Scott being an absolute shitbag? I wouldn’t have thought so, but that hasn’t stopped the franchise from being one of the best examples ever of the “Wow, cool robot” meme, in that its humor, nerd references, and flashy battles are some of the only aspects some fans internalize.

O’Malley has even said in interviews as far back as 2015 that the graphic novels were a time capsule of his early 20s, and that his view on Scott’s story changed as each issue came out. It’s only natural that as people grow up, their work will too. Scott Pilgrim’s final issue dove deep into why its titular hero wasn’t much of a hero at all, whereas the movie was only able to reckon with that in rushed shorthand. Scott Pilgrim Takes Off explores those ideas as well, but it doesn’t have to retread old ground to do it.

But even beyond metatextual retellings, media creators are becoming more comfortable with being less transparent about what they’re putting out, often under the pretense of avoiding spoilers. It’s not entirely a recent development, as Metal Gear Solid 2’s marketing hid the enormous bombshell that Snake wasn’t the game’s main character up until it launched in 2001. More recently, Danganronpa V3: Killing Harmony marketed itself as the series’ first female-led murder mystery, only for it to swap protagonists and become a metatextual reexamination by the end. The Last of Us Part II’s trailers included scenes that did not exist in the game to hide its inciting incident. Even Avengers: Endgame, the second-highest-grossing film of all time, had actors whose characters “died” in Infinity War swearing their characters were gone for good during the film’s promotion, even if they were resurrected by the end of Endgame.

The knee-jerk reaction to this is to claim false advertising, and while I can charitably sympathize with that criticism in some contexts, I do wish we would stop viewing every piece of art we watch, play, or read as a strictly transactional experience. If media companies didn’t feel this compulsion to market everything they put out to the point where everyone thinks they know what they’re getting into before they actually watch, read, or play, maybe the resulting mystique would make audiences more open to experiencing foundational twists that don’t have to be born out of deceptive marketing.

Would Scott Pilgrim Takes Off have played better to certain people if it had been positioned as Ramona’s story from the outset? Maybe. Would there still have been very loud people mad that a woman took the spotlight from a character they only ever saw as themselves despite the text outwardly criticizing him? Absolutely. As someone who really enjoyed Scott Pilgrim Takes Off, even if I had my own disappointment that we’ve still yet to see parts of this story properly adapted, I do hope that some folks can look past their initial expectations and see how the series is additive to the Scott Pilgrim story, rather than just parroting what we can already find in the books.